Including people with learning disabilities in research

Some of our richest insights came from conversations inbetween planned activities

Inclusive research can be scary

Inclusive research makes services better for everyone, not only those with accessibility needs.

As a user researcher, I feel a moral responsibility to create services that work well for everyone who needs them. And since the The Public Sector Bodies Accessibility Regulations came into force last year, public sector teams also have a legal obligation to meet certain accessibility standards. The Government Digital Service (GDS) have made this legislation digestible in a couple of blog posts if you’re interested to find out more.

GDS have also done great work getting public sector service teams to think about inclusion right from the start, rather than something to look at only if there’s time later on. They have embedded it in their standards and guides and are helping service teams put it into practice.

They have looked into why accessibility is still hard for teams. Particularly, the lack of awareness that accessibility is more than just visual impairment and screen readers. Also, that user researchers lack confidence in conducting research with people with disabilities.

I am one of those researchers, despite having done research with people with accessibility needs. I hope sharing my approach can encourage others to conduct more inclusive research despite a lack of confidence and experience.

Overcoming inexperience and fear

In 2018, NHS England asked us to evaluate the part of their website that was intended for people with learning disabilities, their families and carers.

This piece of work was part of a larger round of research. We didn’t have a great amount of time and were working with a tight budget. And, I had never conducted research with people with learning disabilities.

The easy approach would have been to do research with carers and other people who act on behalf of people with learning disabilities. But that would exclude people who live with learning disabilities, whose voices often go unheard. That’s exclusion, not inclusion.

Pushing my fears aside, I decided to find a way around the time and budget challenges.

I started by educating myself as much as possible and seeking advice from people who knew more than me. This gave me a wealth of new knowledge and helped me recognise the gaps in my understanding.

A research paper on the methodological challenges in this area was a great starting point to understand what I didn’t know. This is also the point at which I should thank Jenni from Humanly who gave me some tips on what to think about and who to reach out to.

Working with others for recruitment and support

I approached a number of organisations who work with people with learning disabilities. Choice Support in London had a ‘working group’ of individuals covering a range of learning disabilities, age groups, gender and ethnic background.

We decided to run a workshop with this group. Collaborating with Choice Support meant that we had the right assistance to run this research session effectively and ethically.

Adapting the approach to get strong insights

To meet our time and budget constraints, we designed a half-day workshop with 2 activities: group critique and adapted usability testing.

To get informed consent we created an easy read consent form, as traditional information sheets and consent forms would not meet participants’ needs.

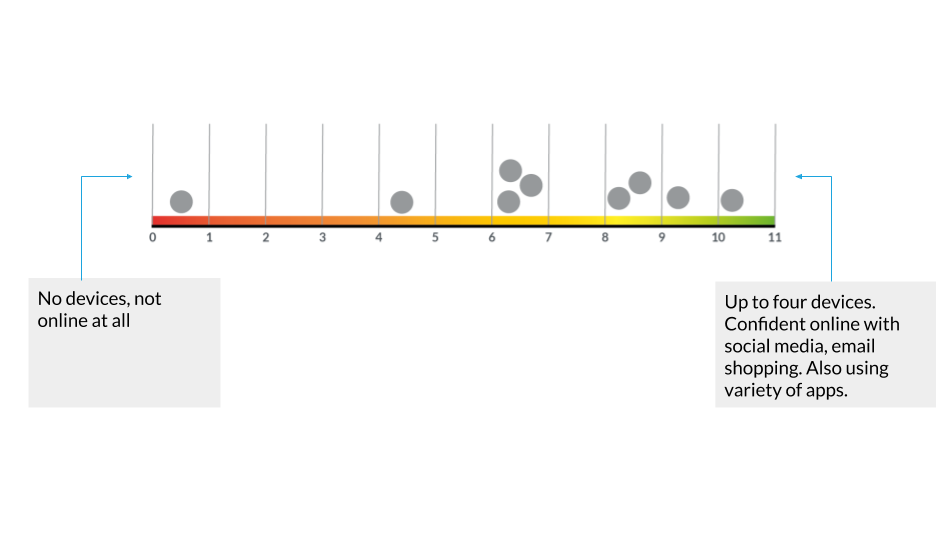

We also designed an easy read digital literacy questionnaire to understand if and how our participants used the internet and assistive technologies. After the participants completed the questionnaire, we asked them to talk us through their answers.

We used the answers to map the participants to a digital literacy index (adapted from the digital inclusion scale for individuals) and to understand how they currently receive NHS-related information. All of this also helped us to assess the validity of our usability test results later on.

Group critique

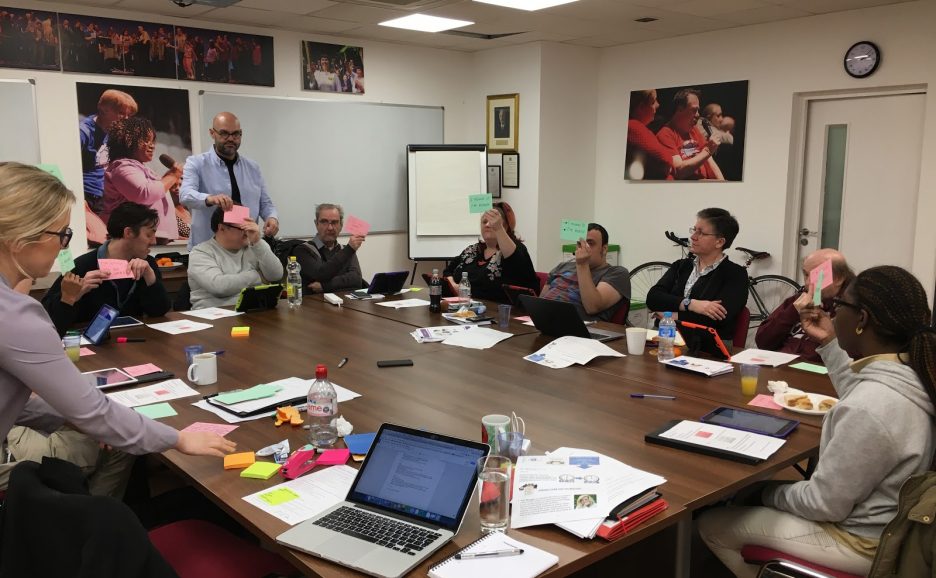

We needed to understand whether the content and design of the pages was useful and legible to the participants. We split them into 3 groups for the first activity, having a mix of ability and confidence. We asked the groups to critique the content and layout of the pages and present back to the rest of the group.

Representatives from Choice support helped 2 of the groups, while we helped the third. We also had an observer in the room to take pictures, notes and generally look out for the comfort levels of all the participants.

Adapted usability testing

We designed 3 tasks to explore the usability of the NHS England web pages and easy-read newsletters. Each participant tried these on a tablet. For each task, we prepared additional visuals to show participants what they should do. We asked them to hold up a card with either ‘I found it. I’m ready’ or ‘I’m stuck. It’s too hard’.

We screen-recorded each tablet, and the facilitator and the observer took notes and photos as participants did the tasks.

Using unstructured time

Some of our richest insights came from the conversations happening in-between the planned activities. This is often the case in research but is even more important for people who might be less confident or able to speak up during group sessions.

What went well and what I would do differently

The careful planning and preparation meant that we got lots of reliable, useful and actionable insights.

And we had lots of positive feedback from the participants about how they enjoyed the “hands-on” tasks. Some of them had previously taken part in consultations and said that they were “boring” and often “hard” because it only involved talking.

However, the critique activity was challenging and a little overwhelming for some participants. We should have broken it up into specific tasks and explained it better with some visual examples of what it might look like at the end.

I would also allow more time for every part of the workshop and set up the tablets the day before to get better quality recordings.

My tips for more inclusive research

- Design with, not for, people with learning disabilities. Let them do more than talking. They are more than capable of contributing to other research activities.

- Push against your inexperience, fear and assumptions. You are (extremely unlikely) to be the first one to do this. And not the only one feeling the fear!

- Don’t do it all yourself. Reach out for support, both to internal research experts and to relevant outside groups. People who care about this type of work will want to help.

- Just start somewhere. Some inclusive research is better than none. And research is never perfect or complete anyway.

- Think carefully about how you give instructions for activities. People with learning disabilities may need more time and different materials than you are used to.

- Add plenty of unstructured time. You want to make sure that everyone has a chance to get involved, and you will get lots of rich and often unexpected insight outside of activities.

- Prepare as much as possible, but have a flexible plan and be ready to improvise during the activities.

With this workshop, we reminded ourselves that inclusive research doesn’t need to be a long and costly expert exercise. With teamwork, some flexibility and a touch of creativity we can make sure that public services are accessible by everyone who needs them.

If you want to know more about how we do user research at dxw then head over to our playbook where we’ve published our principles and workflow.